It was 1933, and Nadezhda and Osip Mandelstam had finally been given a flat of their own, in Furmanov Lane, Moscow. Boris Pasternak came to visit. As he was leaving he said that now Mandelstam had a flat he would be able to write poetry. The remark was passed casually, without forethought. According to Nadezhda Mandelstam in her magnificent memoir, Hope Against Hope, her husband was furious: no true poet, he believed, would be reliant on physical comforts to work.

In response to Pasternak’s remark, Mandelstam wrote a poem that begins: The apartment is quiet as paper. There’s a double irony to this line. Mandelstam composed in his head. When it came to writing his poems down, he needed nothing more than a few minutes, paper, pen and a scrap of bench; mostly the actual writing down was done by his wife, or occasionally someone else. An apartment as quiet as paper: Those words are steeped in threats: with the ubiquity of informers, all walls had finely attuned ears: and in those terrible times, no paper was ever silent or safe.

Mandelstam’s famous poem against Stalin was never written down, it was recited to a small group of friends in May 1934. This poem, now commonly known as his Epigram On Stalin, sent Mandelstam into exile and helped shape his death at a relatively young age. No paper in Stalin’s Russia was silent, but even if it were, the silence of paper is not the silence of poetry.

The Stalinist years were dangerous times, mine are not, and yet these past couple of months as I’ve been sorting through papers and manuscripts to send to a newly-established Porter-Goldsmith archive at the National Library of Australia in Canberra that line of Mandelstam’s, The apartment is quiet as paper, has reverberated in my mind.

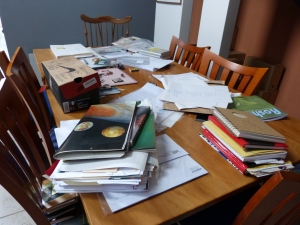

Both Dorothy and I were life-long preservers of paper. It has been a mammoth task this finding, reading, sifting, and cataloguing our stuff. I thought I knew what lay in the cupboards, in boxes, piled in files, on shelves, slipped between the pages of books, the books themselves, I thought I knew because in these past years since Dot’s death, I have, intermittently, dipped into the paper troves and revisited our past. But I knew very little. Casual, spontaneous riffling of a box or a folder of notes as an aide to immersing yourself in a lost life has as little to do with the systematic ordering of the stuff – or bumf, to use one of Dot’s favourite terms – which has characterised these past couple of months

The house is littered with paper. On tables and shelves and scattered across the floor are sheets of manuscript, slabs of book drafts, stacks of magazines, folders of pamphlets and newspaper cuttings; there are letters, cards, notebooks, pocket diaries, and in the cavity beneath the stairs, a jagged and increasing mound of brown archive boxes with the NLA’s name and address on the top. And emanating from it all is the smudged, enveloping silence common to books and paper. When visitors enter this house of paper, I stand and watch them. They must hear it, they must hear the subterranean jangling and shuddering of all this human geology.

Dot threw nothing out, not when it came to paper. Ancient, unused cab charges have been a regular discovery in her old files. When The Eternity Man, the chamber opera Dot wrote with the composer Jonathan Mills, played at the Opera House one Sydney Festival, Dot went to every performance – there were several – and saved every single ticket from those performances. She kept every letter/email pertaining to a gig, even that last one of a series that carried a ‘thankyou’ and ‘I’ll see you soon’. Every advertisement – either for a gig or for one of her books – was shoved into an appropriately named and dated file. And I mean shoved. Dot was all thumbs when it came to folding things – paper or clothes. As for wielding a pair of scissors around a square advertisement, it was an insurmountable challenge.

Many years ago I started using coloured string folders to hold drafts of my novels in progress. I would choose a different colour per book – green for Reunion, pink for The Memory Trap, blue for The Prosperous Thief. The stack of finished drafts would grow in a neat, ordered pile, a vague assertion of control in a process shot through with uncertainty. I suggested that Dot use the string folders too, I even bought the first bundle for her, so her later manuscripts are a little tidier than the earlier ones. But a string folder can only do so much when it comes to a neat bundle, and Dot would pile in drafts with pages non-aligned – a kind of origami nightmare, I found myself thinking as I was straightening up one manuscript a couple of weeks ago.

So much preserved paper has yielded many treasures. Such delight in coming across a good unpublished poem with her fresh, familiar, vibrant voice speaking to me. Her death is irrelevant to the pleasure I derive from these poems; indeed, the only area of my life that has remained untouched by her death is her work. And I’ve found personal bits and pieces, events we shared but I’d forgotten, holidays and weekends away, happenings which at the time I might have glimpsed, but with the papers she kept, now bring a deeper insight and a more poignant punch.

I spent a couple of hours going through two large cartons of my own. I have lugged these cartons from house to house over a period of four decades. Like Dot, I kept everything. Notes and cards from primary school friends, from teachers, from anyone who bothered to notice me and address me on paper are stacked in an old shoe box, itself in the bottom of one of the cartons. Purple and gold crepe streamers kept from not one but two Wesley school dances have been preserved in neat rolls. Invitations to birthday parties, letters from school-friends. I’ve kept early scribblings, (how good, I wonder wryly, do early scribblings need to be before they’re called ‘juvenilia’?), faded photos of friends whose names I’ve forgotten. Like Dot, I have thrown nothing out, I’ve just stored the stuff more tidily than she did. Although not when it concerns dating and labelling. Dot was a stickler for completeness. Everything of hers has been dated and located. So, for example, every draft of every poem carries the date of its composition and the name of the house, the hotel, the coffee shop and/or suburb or city in which the writing occurred.

Driven by hopes for posterity, there are writers who keep everything (I’ve even heard about writers who spend the fallow months between books copying out manuscripts by hand in order to enhance the value of their papers). But not for me and nor, I believe, was this the case for Dot. I started stockpiling my life long before I knew what my future would hold. Yes, I knew I wanted to be a novelist from my earliest years, but this was a secret desire, more in the way of a fantasy to make the childhood years more bearable. I had no thought of being a writer as I carefully stashed away those invitations and notes and jottings. And I expect it was much the same for Dot.

I wonder now if there is something about paper and the ephemeral nature of imaginative work that has we writers hoarding paper even before we know what our future will bring. Prior to our current era of on-line living where anything and everything is preserved (and made public), perhaps writers in pre-digital times announced themselves in primary school because of the paper they stashed away. Perhaps this hoarding, revealing as it does a value, even a reverence directed specifically to paper and the written word, used to separate the future writers from the future musicians and accountants and plumbers. And it’s not just the paper itself, but what it symbolises in terms of memory. After all, these papers and keepsakes are mementoes – monuments and records – and memory is the fiction writer’s stock in trade. The novelist creates characters, s/he gives them childhoods and adolescences, families and lovers; the novelist creates narratives out of how the past shapes a character’s life in the present and on into the future.

I work slowly in the silent house. Occasionally I’ll hear an explosion, a cry of delight coming from me as I find a never-before-seen good poem. I’ll read such poems aloud, just as I used to when Dot would hand me a draft of a new poem. I would read it silently at first, then if it was very good or if there was a bit of a clunk, I’d read it aloud to her. Listen, I used to say, listen to me read it. And she would sit on the couch, her head cocked to one side in that characteristic listening pose of hers while I read.

You need quietness and stillness, you need background silence to hear voices. You need silence for memories, ideas, the past and the future to break through the surface of consciousness. The silence of paper: there is nothing richer, nothing more vibrant. Not even life itself.